Red blood cells (RBCs), or erythrocytes, are the most abundant cells in human blood and are fundamental to life. Their primary role is to transport oxygen from the lungs to tissues and organs and return carbon dioxide to the lungs for exhalation. With a lifespan of around 120 days, RBCs are constantly being produced and recycled in a finely tuned system that keeps your body functioning efficiently. Their structure, composition, and function make them uniquely suited to their role, and understanding RBCs is central to hematology.

What Do Red Blood Cells Look Like?

RBCs are small, flexible, and biconcave, meaning they are round with a central indentation. This shape increases their surface area-to-volume ratio, maximizing their ability to absorb and release oxygen. It also enhances their flexibility, allowing them to squeeze through capillaries as small as 3 micrometers in diameter, smaller than the cell itsel

- Size:

At about 7-8 micrometers in diameter and 2 micrometers thick, RBCs are microscopic. Despite their tiny size, their surface area is large enough to optimize gas exchange throughout the body. - Membrane:

The RBC membrane is a thin, lipid-protein bilayer that protects the cell while remaining flexible. This membrane is semi-permeable, allowing the exchange of gases and nutrients while maintaining the cell’s integrity. The proteins in the membrane also include antigens that determine your blood type (A, B, AB, or O), which are critical in transfusion medicine. - Cytoskeleton:

Beneath the membrane lies a network of structural proteins, primarily spectrin, which forms the RBC cytoskeleton. This framework provides both durability and flexibility, enabling RBCs to deform and recover their shape as they travel through narrow and winding capillaries.

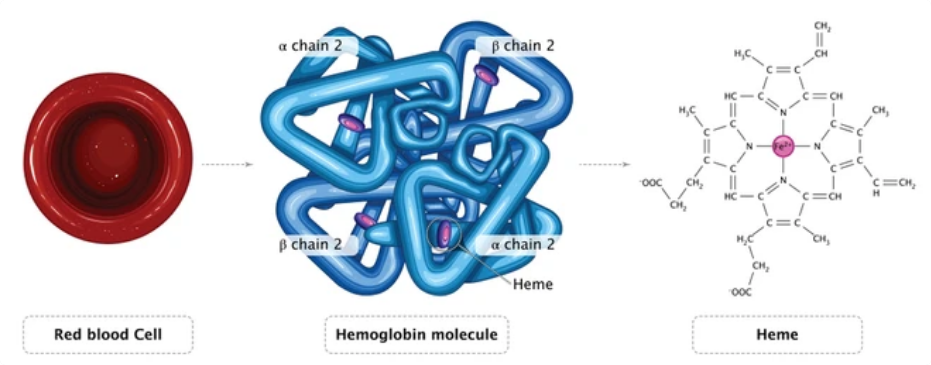

- Hemoglobin:

RBCs are densely packed with hemoglobin, an iron-rich protein that binds oxygen in the lungs and releases it to tissues. Hemoglobin also carries a portion of carbon dioxide from tissues back to the lungs. Each hemoglobin molecule can carry up to four oxygen molecules, making it an incredibly efficient transporter.

- Nucleus-Free Design:

Unlike most cells, RBCs lack a nucleus and organelles, which allows them to dedicate maximum space to hemoglobin. However, this design means they cannot repair themselves, limiting their lifespan. - Carbonic Anhydrase:

RBCs contain the enzyme carbonic anhydrase, which facilitates the conversion of carbon dioxide and water into carbonic acid. This reaction is essential for transporting carbon dioxide and regulating blood pH levels.

How Are Red Blood Cells Made?

The production of RBCs, called erythropoiesis, occurs in the red bone marrow, primarily in the ribs, vertebrae, pelvis, and sternum in adults. It is a carefully regulated process influenced by oxygen levels in the blood.

- Initiation:

RBC production begins with multipotent hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow. These stem cells differentiate into erythroblasts, which are early-stage RBCs. - Hemoglobin Synthesis:

Erythroblasts actively produce hemoglobin, preparing the cell for its oxygen-transporting role. - Maturation:

During maturation, the erythroblast expels its nucleus and organelles, becoming a reticulocyte. This step optimizes the cell for oxygen transport by creating more room for hemoglobin. - Release into the Bloodstream:

Reticulocytes enter the bloodstream and mature into fully functional RBCs within 1-2 days. - Regulation by Erythropoietin:

The process is regulated by the hormone erythropoietin, which is produced by the kidneys in response to low oxygen levels in the blood. Erythropoietin stimulates the bone marrow to increase RBC production, ensuring oxygen demands are met.

The Lifespan and Recycling of RBCs

RBCs are incredibly resilient but are designed to be temporary. After about 120 days, their membranes become less flexible, and they are marked for recycling.

- Breakdown:

Old RBCs are removed by macrophages in the spleen, liver, and bone marrow. This process prevents damaged cells from clogging the bloodstream. - Recycling:

- Iron: Extracted from hemoglobin and stored in the liver or used to produce new RBCs.

- Heme: Converted into bilirubin and excreted in bile, giving feces its characteristic color.

Functions of Red Blood Cells

- Oxygen Transport:

RBCs bind oxygen in the lungs via hemoglobin and release it to tissues where it is needed for energy production. - Carbon Dioxide Transport:

RBCs transport carbon dioxide back to the lungs, primarily as bicarbonate ions formed by the action of carbonic anhydrase. - pH Regulation:

By buffering hydrogen ions, RBCs help maintain blood pH within a narrow range, crucial for enzyme activity and overall metabolic stability.

When Red Blood Cells Go Wrong: Hematological Disorders

Anemia:

A condition where RBCs or hemoglobin levels are insufficient, leading to reduced oxygen delivery.

- Types:

- Iron-deficiency anemia.

- Vitamin B12 or folate-deficiency anemia.

- Hemolytic anemia, where RBCs are destroyed prematurely.

- Symptoms: Fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath.

Sickle Cell Disease:

A genetic disorder where RBCs take on a rigid, sickle-like shape, reducing their flexibility and lifespan.

- Impact: Blockages in blood vessels, pain, and organ damage.

Polycythemia:

An overproduction of RBCs, which thickens the blood and increases the risk of clots.

- Causes: Bone marrow disorders or low oxygen levels (e.g., at high altitudes).

Thalassemia:

A genetic disorder affecting hemoglobin production, resulting in smaller and less effective RBCs.

Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria (PNH):

A rare disorder where RBCs are destroyed prematurely due to defective protective proteins on their surface.

Why Understanding Red Blood Cells Matters

Red blood cells are more than just oxygen carriers—they are central to your body’s ability to function. From regulating pH to influencing your immune system and overall health, their impact is far-reaching. By understanding RBCs, we gain insights into the delicate balance of health and disease, making it easier to diagnose, treat, and manage conditions effectively.